From Jon Canter's Guardian tribute to Douglas Adams:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/aug/09/afterliff-douglas-adams-jon-canter

Your party of 12 finishes its meal. The bill is passed to the one among you who's the best at mental arithmetic. "Twenty-six pounds each, including service!" they shout – to which, inevitably, someone responds "Does that include service?" Then another inevitable thing happens. You all place notes and coins in the middle of the table. Some of you remove notes and coins as change. Then a volunteer counts the assembled money. Logically, since you've each put in 26, there has to be £312. But there isn't. There just isn't. Instead, there's a bodmin, as defined by The Meaning of Liff as Bodmin (n.) The irrational and inevitable discrepancy between the amount pooled and the amount needed when a large group of people try to pay a bill together after a meal.

The article continues:

The Meaning of Liff (1983) was a comic dictionary written by Douglas Adams and John Lloyd, who invented hundreds of such "liffs" – a liff being a common experience, feeling, situation, object or kind of person for which no word existed. Liff, as all Dundonians will tell you, is also a hamlet north-west of Dundee. But to Adams and Lloyd, who recycled place names for all their definitions, Liff was just one of those "spare words which spend their time doing nothing but loafing about on signposts". And so Bodmin stopped loafing about on signposts in Cornwall and went to work as a universally recognisable group-dining experience which now, at last, had a name.

In the winter of 1989, Adams hired a house on Palm Beach, just north of Sydney, and invited Lloyd and various friends to join him. I was one of those friends, having known both men since we were students in the early 70s. The two men got down to writing their sequel, The Deeper Meaning of Liff. Or rather, they didn't. Instead, Douglas, a famous procrastinator, enjoyed various friendly conversations with his various friends. After much cajoling by Lloyd, a man of discipline as well as talent, Douglas sat by the pool looking miserable and occasionally writing things down – which is virtually the dictionary definition of comedy writing. (Apart from the bit about the pool, of course, which only applies to comedy writers as successful as Douglas.)

Was I just going to sit there, storing up anecdotes about their liff-writing crisis? No. As a comedy writer myself, I lobbed in the odd liff. Gribun (n.) The person in a crisis who can always be relied on to make a good anecdote out of it. The Deeper Meaning of Liff duly came out in 1990 and the UK editions of the two books have sold nearly 400,000 copies. But the two men, sadly, won't be writing any more. In 2001, when he was 49, Douglas died of a heart attack.

Last summer I recieved an email from Lloyd, now the Baftastic producer of Not the Nine O'Clock News, Blackadder, Spitting Image and QI. He asked me to co-write a new volume of liffs. It would be called – with an affectionate nod to our absent friend – Afterliff. He told me he'd like it to embody "the spirit of Douglas". I was overwhelmed. Douglas was a departed genius. Capturing his spirit would be like trying to emulate Freddie Mercury. Could I hit the high notes in Bo Rhap? Could I wear the white vest? Could I do that thing he did with the mic without poking myself in the eye? Then I calmed down. This was nothing like replacing Freddie Mercury in Queen. This was like stepping into your ex-flatmate's rather large shoes. It was weird but it was destiny. I thought about it, for just under a second, and said yes.

As a flatmate, the 6'5" Douglas did everything on an epic scale, from buying Coca-Cola (in crates) to making 13 successive phone calls on the subject of the new Paul Simon LP. And then there were the baths. The baths! Sometimes he was in there for an hour and a half. If he wasn't in the bath, he was getting out the bath, or planning to go back in. It's a miracle he didn't shrink. That bathroom door, shut against me. Who hasn't had a flatmate like that? On my first day at the liff wordface, I saw, in a gazetteer of French place-names, Beaucroissant. A spirit-of-Douglas liff hit me like a towel. (You may recall, from The Hitch‑Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, that a towel not only provides warmth "as you bound across the cold moons of Jaglan Beta". You can also "wet it for use in hand-to-hand combat".) Of course. The towel-obsessed Douglas was a Beaucroissant (n.) A male flatmate who spends all his time in the bathroom.

The Big Man, as John and I always call him – with our devastating writerly insight – was a beguiling mix of the macro and the micro, a cosmic thinker frequently stranded between The End of the Universe and the end of the sentence, which he couldn't quite bring himself to write. Brampton Bierlow (n.) The chuntering noises made by an old photocopier to let you know it's thinking about doing something. "Thinking about doing something": in its pathos and its bathos, its putting off of the thing it's meant to do – in his case, write – that's as Douglas as bath-steam.

The old photocopier, though, is not Douglas. The man was fascinated by new technology, new ways of generating and disseminating information. He'd want Afterliff to define those 2013 tootgarooks who never once feel fowey as they stare at the sorrento. (Tootgarook (n.) One who retweets praise about himself; Fowey (adj.) Filled with self-loathing and despair after six hours surfing the internet; Sorrento (n.) The thing that goes round and round as a YouTube video loads.) But it's not just the content that's evolved for an interactive age. The methodology has too. Liffmaster Lloyd has adopted and adapted liffs from Douglas's website h2g2.com, from his own website qi.com, from listeners to the Radio 4 programme The Meaning of Liff at 30, from competitions run by Douglas's brother James to raise money for Save the Rhino. Who knows? Next year, we might be sourcing them at Glastonbury. If John and I went out for a meal with everyone who's contributed to Afterliff, there'd be the most humungous bodmin.

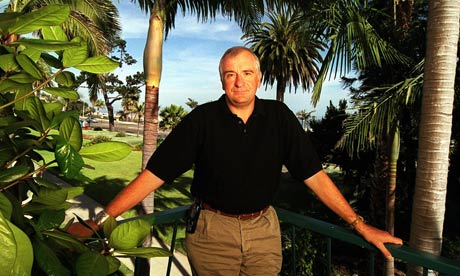

The Big Man … Douglas Adams pictured at home in Santa Barbara in 2000. Photograph: Dan Callister/Getty Images

No comments:

Post a Comment