http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2010/jan/23/ian-jack-burns-night

Here's to a rare thing: a genuine popular festival with no commercial strings attached

- The Guardian, Saturday 23 January 2010

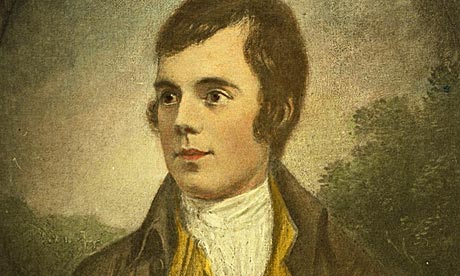

Ian Jack's family - like so many others in Scotland – kept a portrait of Burns in the home. Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty

Not so long ago, when London taxi drivers still frowned at Scottish banknotes, haggis wasn't an easy food to find much farther south than Tyneside, and for most of the year this largely unregretted scarcity still prevails. Apart, that is, from the month of January, when over the past decade or so increasing numbers of the pale obese sausage – a sausage in need of a gym – have begun to appear in the windows of London butchers' shops as a reminder that the birth anniversary of Robert Burns is just around the corner. As a fresh retail opportunity, the Burns Supper is hardly up there with Halloween; 25 January is too close to Christmas and apart from haggis, and assuming there's left-over whisky in the cupboard, what's to be bought other than a turnip? The Burns Supper in England may be a rare example of a festival that has grown in popularity without the push of commerce.

They can be ghastly occasions. Helen Simpson brilliantly catches the atmosphere of too many of them in her story, Burns and the Bankers. A great crowd of kilted men and their unhappy wives gathers in the ballroom of a Park Lane hotel, where the Federation of Caledonian Bankers is to celebrate the bard. The haggis is addressed ("on and on it went, incomprehensible … and smug and ridiculous"), the Immortal Memory proposed, the Lassies toasted ("Oh what windbags the Scots are, thought Nicola … what blowhard old windbags they really are"). And the men drink too much whisky and get ever more pleased with themselves.

As a junior reporter on a Lanarkshire newspaper, I knew one or two evenings like that: the Cambuslang golf club in 1966, for example, followed the same pattern, though its supper obeyed tradition and included no women. I don't remember that the Immortal Memory, the eulogy, was to "Burns the golfer" but it would have been no surprise if the speaker had imagined a link between the poet and the game. A speech along the lines of "What Burns would have been like as a golfer" is by no means improbable, his characterisation being so famously malleable. Burns the ploughman, Burns the romantic lover, Burns the Freemason, Burns the Scottish nationalist, Burns the international socialist, Burns the rebel, Burns the loyalist, Burns the drinker: all these personalities have been promoted and contested. At school, the man who taught us English was a big Burns enthusiast and also, awkwardly, a member of the temperance society known as the Rechabites after a tribe of total abstainers in the Old Testament. "Boys," he would say, "I ask you, how could a poor man on £40 a year afford to be a drinker?"

The temptation here is to mock Burns Suppers as an example of what historian Hugh Trevor-Roper called "invented traditions", a ritual that like Druidism, clan tartans and eisteddfods is essentially a Victorian reimagining of the past. But the historical record demolishes that idea. The memorialisation of Burns began only a few years after his death in 1796. There were Burns Clubs in the west of Scotland by 1805, a mausoleum in Dumfries by 1817, a monument (the foundation stone was laid by James Boswell's son with "full Masonic honours") started at his birthplace in Alloway, Ayrshire, in 1820. As to Burns Suppers, the first was held at his old Alloway cottage in 1801 and for several years commemorated his July death as well as his January birth. From the beginning, speeches were made to the poet's "immortal memory" – many guests had known him – and haggis featured on the menu as well as sheep's head.

The cottage, which the Burns family quit long before, had been converted to an alehouse and soon began to attract literary pilgrims. Keats, visiting in 1818, wrote to a friend: "We went to the cottage and took some whiskey … The man at the cottage was a great bore with his anecdotes – I hate the rascal – his life consists in fuz, fuzzy, fuzziest – he drinks glasses five for the quarter and twelve for the hour, – he is a mahogany faced old jackass who knew Burns – he ought to be kicked for having spoken to him."

As an after-death cult, Burns's was almost instant, and like all successful cults it had objects and places that followers could visit and feel attached to. Apart from the cottage itself, a marvel of humility, there was the River Doon of Ye Banks and Braes and the Brig o' Doon and the kirkyard where Tam o' Shanter had come unstuck. Long before Shakespeare's birthplace was saved for the nation in 1847, after the showman PT Barnum had announced his intention to ship it to America, Burns worshippers had a geographical focus. Wordsworth readers had to wait 50 years after the writer's death until Dove Cottage was open to the public; Keats had been dead a century before his house in Hampstead became a museum; the last Brontë sister died in 1855, but only in 1928 did the Haworth parsonage fall into the hands of the Brontë Society.

As well as prefiguring (and outnumbering) the literary tourists of other writers, early Burnsians were far more fervent. Religiously, they sought relics – and not just the poet's inkbottles, doorknockers and snuffboxes, most of them as spurious as nails from the cross. At the various sites of his career, souvenir-hunters stripped away pieces of bushes and trees and kept them labelled in glass cabinets. Paper-knives were fashioned from old Burns skirting boards and egg-cups from old Burns rafters, or least from wood alleging that provenance. After souvenirs began to be mass-produced later in the 19th century, the range of Burns's iconography became overwhelming. It could be safely asserted that no other writer has been remembered by so many different objects – from cigarettes to teaspoons – in so many parts of the world. Australia has nine statues and the USA 16; Atlanta got a full-scale reproduction of his Alloway cottage in 1910.

This meant that he was phenomenally present in quite ordinary Scottish households. My own not untypical home contained, as well a comprehensive edition of the work, a rough copy of his Alexander Nasmyth portrait, a picture of a plough, and an embroidered motto wishing that some power would give us the gift to see ourselves as others see us. Other homes had busts, Tam o' Shanter jugs and models of "The Cottage". How? Why? Some people put it down to "the psychopathology of a stateless nation". Professor Rab Houston of St Andrews University argues that, at a time of great social change, Scottish readers found in the ruralism and romance of Burns "a symbol of an allegedly uncorrupted Scotland".

Equally, he was an original and wonderfully memorable and quotable poet. Not for nothing did Keats and Wordsworth come knocking at his memorials. Faced with the "mahogany faced old jackasses" who inhabit the drunker parties of the January carnival, we should take a leaf from Keats and remember good poems that in their liveliness and sympathy have made Burns the most genuinely popular of British poets.

For good measure, here's the Burns poem we're probably all most familiar with, if only as the source of Steinbeck's title Of Mice and Men. I'm including both the original and a version in standard English.

http://www.worldburnsclub.com/poems/translations/554.htm

To A Mouse.

On turning her up in her nest with the plough, November 1785.

Burns original:

| | | ||||

| Wee, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie, Standard English translation:

|

No comments:

Post a Comment