All the president's women

Chris Petit is intrigued by a clinical take on JFK that connects twin pathologies of disease and scandal

- The Guardian, Saturday 11 April 2009

It seems so obvious that one wonders why no one has done it before - to take a novel, clinical approach to John F Kennedy as a case study in philandering and psychosexual pathology, conditioned by a history of medical illness that required a plethora of drugs to maintain the illusion of vigour and rude health necessary to his image of political dynamism and change when in fact he could barely walk and was incapable of putting on socks and shoes without help.

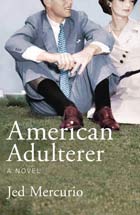

- American Adulterer

- by Jed Mercurio

- 354pp ,

- Jonathan Cape,

- £12.99

Kennedy was nothing if not a chemical man, at little more than 40 already treated variously for Addison's disease, thyroid deficiency, gastric and urinary ailments, venereal disease, high cholesterol, allergies, asthma, lumbar vertebral collapse, osteoporosis and osteoarthritis, which resulted in his being forced to wear a back brace (and which contributed to his death because it held him rigid and left him incapable of ducking the second shot, to his head). Cortisone puffed his jowls, and Addison's was evident in a permanent tan with a yellow tinge. Kennedy swallowed pills until "his blood simmered with chemicals", and was shot up with enough drugs, including testosterone, for Mercurio to speculate (unlike Kennedy's official doctors) on whether the severe hormonal dysfunction was responsible for his extraordinary libido and satyriasis.

He famously told Harold Macmillan that if he went without a woman for three days he got terrible headaches. He therefore learned early in life to read women's availability. As president, a hectic political schedule and back spasm excused him the "drag of foreplay". Sexual agility was not on offer; possession and dismissal being uppermost in his mind, a call to a legion of women to perform their patriotic duty. Mercurio speculates only briefly about what it might have been like to be on the receiving end of such attention. Sex was the subject's golf, he notes drily: "a couple of quick holes, getting around as quickly as possible".

Treating his subject in diagnostic terms, Mercurio - a doctor and author of the hospital drama Bodies, one of the best British TV shows of recent years - suggests that the sexual career, instead of being a sidebar, was the key, and that the fate of the free world was determined by a maverick rather than "the juggernaut of conventional morality" that he publicly espoused. Mercurio presents JFK as a liberal hero, rather than a hypocrite, just the man for those times, a fascinating synthesis of surrogate motive and political vision, driven by the double standards now evident in TV shows such as Mad Men and even The Sopranos (whose central marriage was always very Kennedy-like in terms of what the wife chose not to know and the husband not to tell).

JFK has been fictionalised by James Ellroy and DM Thomas, among others, but not with material that hovers on the edge of straight-faced farce. Cross-cut with major public events, and somewhat lazily illustrated with long quotes from Kennedy's political speeches, the book's parallel track shows life and career as controlled exercises in stage-management. Failure threatened exposure, which would have led to the shameless being shamed. With hindsight, there were plenty of clues to the real state of things: Kennedy's explosive bowel, which interfered with his duties, and ensuing embarrassing toilet sessions; his serial womanising matched by his wife's compensatory, uncontrolled spending; the two of them being shot up with speedball cocktails by a quack known as Dr Feelgood, who accompanied them unofficially on their state visit to France and whose regimen helps to explain why in photographs they look, well, so out of it, while managing, just, to appear focused for the camera.

Kennedy's marriage and his wife's instability, plus relations with Frank Sinatra and his affair with Marilyn Monroe, are treated with clinical insight, but notables are missing, particularly his brother Robert (which is a surprise, given that he took on Monroe after Jack had dumped her). Mercurio knows that any obsession, however fascinating, risks becoming tedious; and despite his best efforts to present Kennedy in a forgiving light, the man remains less than the sum of his parts - smart enough to know there was a void in the centre of his life but incapable of transcending the monomaniacal intensity that gripped him. Seen through his predatory, telescoped eye, all women were reduced to the sum of his prescriptions. Mary Meyer, especially, here relegated to a cameo, deserves more, being more interesting than her lover - a woman of independent spirit who smoked dope (noted) and took LSD with Timothy Leary (not noted), and came closest to destabilising the philanderer's equilibrium. She was later murdered under bizarre circumstances, and her diary, detailing their affair, threatened briefly, until it was confiscated, to become a political hot potato.

Mercurio's thesis includes the interesting speculation that Kennedy was saved by his assassination, being already a doubly marked man. According to his doctors, he didn't have long to live, and if disease hadn't finished him scandal would: the FBI had an extensive dossier on his sexual peccadilloes and, following the Profumo affair in England, he was no longer safe from the press. Scandal had become a new and powerful market force, and Kennedy knew he was next.

If only I had known this information during GCSE's... my history essay could have had a whole new twist.

ReplyDeleteAs I remember, your history essay on Kennedy/Johnson was controversial enough as it was. I almost drove through the entry barrier at Tesco while I was listening to you recount what you had written.

ReplyDelete