Melting Cathedrals & Fairytale Houses

Article by our guest writer M. Christian (from "Meine kleine fabrik"). M. Christian writes about odd, weird, and wonderful things - most of them are, just like life itself, as unexpected as possible

I thought I was on drugs.

Not that I knew what being on drugs was like, you understand. I was, after all, a pretty clean-cut, mostly-normal, teenager spending a fairly-uneventful summer bumming around Europe: London, Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam, Athens, and so on in no particular order.

Then I turned a corner in Barcelona -- and was sure someone at the hostel the night before had slipped me something.

What other explanation was there? A building was melting for God's sake!

(image credit: Vincenzo)

The rest of the street was Spanish normal: warm brick facings, black toothed iron railings, arched windows, bursts of flowers on balconies, but right in the middle of average, of ordinary, of common, of commonplace was a building that sagged, that drooped, that arched, that ... well, that looked like it had been designed with vines and leaves in an orchard instead of with a T-square in a boxy office, planted from a seed and cultivated instead of having been mathematically assembled brick by stone cold brick.

(image credit: Tato Grasso)

(images credit: Daniele, Ruth Weal)

I'd heard of Antoni Gaudí, of course, but for some strange reason I either hadn't made the connection between the eccentric architect and his hometown, or, more than likely, hadn't a clue how brain-throbbingly amazing his work was. But, drugs or no drugs, standing slack-jawed in front of the flowing glory of Casa Batlló on 43 Passeig de Gràcia, I decided I'd spend the next few days seeing as much Gaudí genius as I could.

"A Nut, or a Genius?"

Barcelona has become Gaudí's city, which is ironic since Gaudí didn’t start out as the city’s cultural icon. Far from it: for a long time his only real supporter was the very-rich Eusebi Güell. It was only much later that the city, and Gaudí's critics, finally began to understand what he was doing.

Park Güell -

Just look at his Park Güell (named after you know who), just a short walk from Casa Batlló, up on el Carmel hill: everything in the park … flows -- like the concrete he used had been trapped, mid-liquid, as it cascaded down toward the city. Benches are part of fountains which are part of walls which are part of stairs which are part of terraces which are part of columns -- Güell created a run-on architectural dream, an organically shaped wonderland for the city.

(image credit: Santi)

(image credit: Angelo Cesare)

(image credit: moosoid9)

(image credit: Mikael Adolfsson)

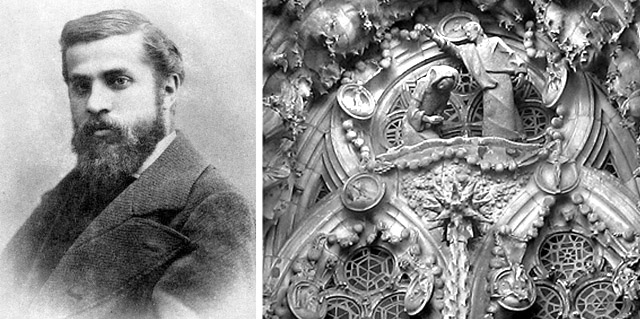

Before continuing in my footsteps, here’s a bit more about Gaudí: an average student at the Escola Tècnica Superior d'Arquitectura in Barcelona, supposedly his instructor signed his architecture diploma saying "Who knows if we have given this diploma to a nut or to a genius. Time will tell."

While time certainly did tell, Gaudí at first didn’t have an easy time of it. Fortunately for the world, Güell took those early risks with the eccentric architect and gave Gaudí a chance to put into reality the brilliance growing in his mind.

Casa Milà -

Just look at his Casa Milà (aka La Pedrera): nothing about it looks assembled, or built. Instead it looks like Gaudí plopped it there as a huge mountain of slippery clay then dug his thumbs and fingers into it to make windows, doors, balconies, and even chimneys.

(image credit: Eugene Zhukovsky)

(image credit: Claude)

The Unfinished Cathedral

These days green is the buzzword and organic is the phrase-of-the-moment: designers and builders from Berlin to Saudi Arabia are putting down their angles and degrees for sea shells and bird’s wings, but all of them owe their biological inspiration to Gaudí. Here’s the man himself on the subject: “The architect of the future will build imitating Nature, for it is the most rational, long-lasting and economical of all methods.”

There’s one very important detail I left out of my very short bio of Gaudí. To fill that in let’s go back in time to when his Park Güell was finished: the men are dapper in their black suits and high waistcoats, the women are splendid in their flowing skirts and elaborate hats, and the streets flow with horses (because automobile hasn’t been invented yet).

(image credit: Arutha)

Sure, green is on everyone’s lips today, but Gaudí was creating mad masterpieces of organic shapes, living forms, and natural contours starting in 1883; Park Güell was finished in 1907.

One more stop, one more building -- even though Gaudí has grown lots more in Barcelona. Believe me, though, this one is worth the wait.

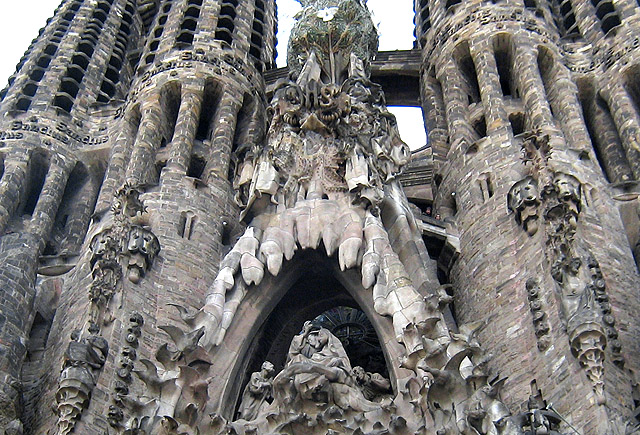

By the time he began working on the Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família, Gaudí was a legend but by his 40th year of working on it, both Barcelona and Gaudí had fallen on hard times. According to some, Gaudí had grown so eccentric, so raggedy, that cabs refused to pick him up, assuming he was a tramp.

(image credit: Santiago Cer)

Gaudí never saw the Sagrada Família finished. In fact no one has because, to this day, it’s still a work in progress. When Gaudí died in 1926, after being hit by a streetcar no less, the Sagrada Família had only just begun to show its potential.

There’s only one way to describe the Sagrada Família, what was to be -- and one day will be -- Gaudí’s masterpiece: it’s a cathedral.

(image credit: Stjepan Felber)

(image credit: Truus Stotteler, new sculptures designed after Gaudi's death by Josep Subirachs)

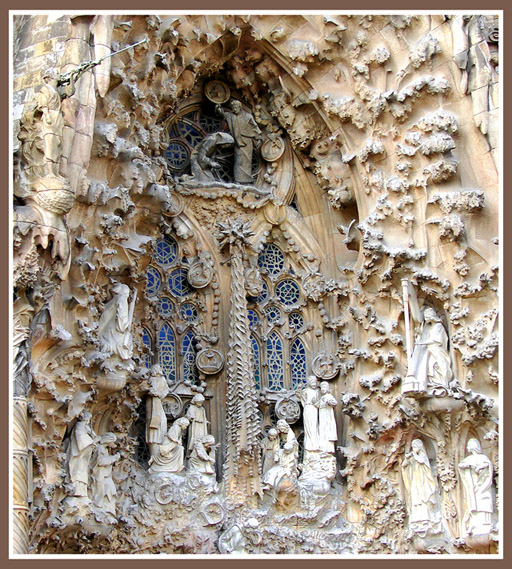

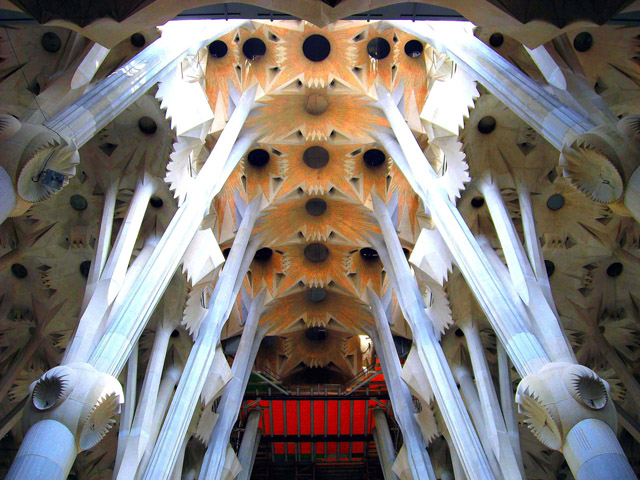

Sitting in the center of Barcelona, the Sagrada Família is a drip-sand castle, a towering bone-ribbed, seashell-vaulted, tower 170 meters tall (about 500 feet for us Americans). An ardent Catholic, Gaudí envisioned his cathedral to be his final statement, a perfect combination of natural shapes with inorganic materials, a crowing celebration of the beauty of living things.

(image credit: Rüdiger Marmulla)

Here is a great photo set, showing how the Sagrada Familia looks inside.

(image credit: Jeroen van Wijngaarden)

And a rather impressive manipulated rendition:

(image credit: J. Salmoral)

It’s amazing to realize Gaudí did what he did at the turn of the last century, but it’s absolutely stunning when you realize that this architect’s masterpiece, if all goes as planned, will be finished in 2026.