I was led to Aleksander Hemon's novel The Lazarus Project by Adam Mars-Jones's review in the Guardian. My husband often comments ruefully that I spend more time on the opinions of critics than reading books or watching films. Probably true, but the reviews I pay most attention to are the enthusiastic ones: I'm not put off by carping criticism, but I am willing to take a chance on a novel/movie/CD/restaurant that a reviewer raves about. Over the years, of course, this policy has occasionally led me astray, but on the whole, I think the triumphs have significantly outnumbered the failures. Michael will eventually forgive me for the days he wasted on Foucault's Pendulum....

The remarkable fact about Hemon that is flagged immediately in any discussion of his work is that, despite his virtuosity in English, he is not a native speaker. This MacArthur Foundation "genius," born in 1964, came to Chicago from Sarajevo in 1992. In The Lazarus Project, he uses the historical records of the 1908 killing of Lazarus Averbuch by the Chicago chief of police as an imaginative prism to examine his Bosnian narrator's post-9/11 sense of dislocation. The resonance of the anti-immigrant, anti-socialist hysteria of the first decade of the twentieth century with the first decade of the present century requires no authorial comment, and Hemon avoids unnecessary overstating of parallels.

Averbuch was most likely unarmed when he knocked on the door of Chief Shippy's mansion; Emma Goldman's imminent arrival had created anarchist paranoia in the forces of law and order. Alienated writer Brik (very tempting to see as the author's doppelganger) uses Lazarus's sister Olga as the human face of the 1908 story, which alternates with his own, a hundred years later. In the present-day story, he uses his quest for background material in Moldova, the former Bessarabia where a pogrom drove the Averbuchs into exile, as an excuse to revisit Sarajevo. His companion is Rora, the photographer, storyteller and war veteran whose sangfroid underscores Brik's inveterate navel-gazing.

Hemon studied Nabokov's works to finetune his English, and the influence shows. He is more restrained, however, in his use of arcane vocabulary. What impressed me most in this picaresque tale of philanthropists and gangsters, anarchists and doctors, is the energy and powerfully original use of compressed language: "a couple of bronze Soviet soldiers cast in victorious eternity" (p.203). Having spent six weeks this autumn in Kazakhstan, I know exactly what he means. Hemon's prose is as muscular as these statues.

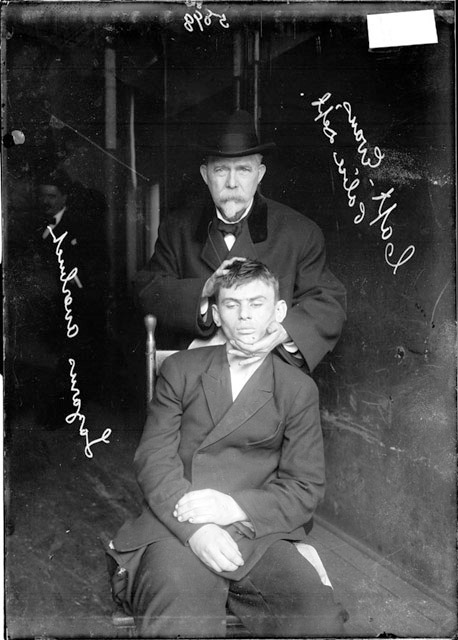

The hardback version of The Lazarus Project is also beautiful, with photos from the Chicago Historical Society alternating with those taken by Hemon's own real-life sidekick, the photographer Velibor Bozovic. In this case, I wouldn't wait for the paperback.

Lazarus Averbuch, deceased (front)

Photo from: http://homicide.northwestern.edu/crimes/lazarus/scenephotos/averbuchfront/

"Prose this powerful could wake the dead." Adam Mars-Jones.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/aug/10/fiction1

No comments:

Post a Comment